Luther on Drowning People

The year 1525 was not a happy one for the burgeoning Protestant Reformation.

Early on in 1525, the Reformers noticed that in some communities, the exciting new notion of religious liberty could give way to what they perceived as excess. Inspired by the success of Luther, some people were willing to adopt ideas the Reformers themselves considered heretical, which put them in the uncomfortable position of having to deal with heresy without resorting to the coercive tactics of Rome.

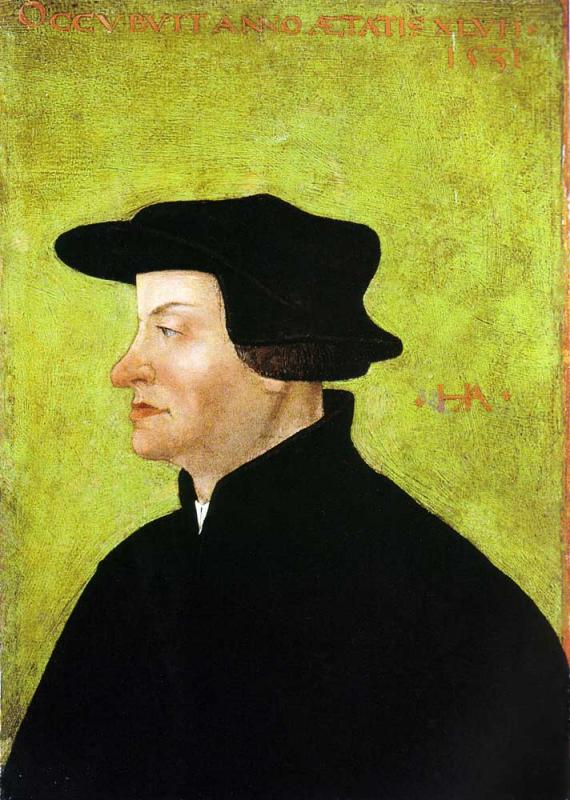

In Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli was greatly perturbed by the teaching of the Anabaptists, who insisted that infant baptism was neither biblical nor practiced by the early church. They were rebaptizing adults (although the Anabaptists argued that it was not a rebaptism at all, since the candidates had never been properly baptized). But it wasn't the baptisms that bothered Zwingli nearly as much as the Anabaptists' insistence that the proper relationship between church and state was utter separation.

The Reformation had yet to proceed that far.

Having separated from Rome, the Protestants didn't have a mechanism through which to deal with heretical teachings. Rome had canon law; the Protestants had barely organized. Zwingli turned to Roman law to find a solution, hitting upon a solution that powerfully illustrates why the feet in Nebuchadnezzar's dream (Daniel 2) had Roman iron mixed with European clay: the influence, policies and culture of Rome persisted long past the collapse of the western empire in 476 AD.

After Constantine Christianized the empire early in the fourth century, he dealt decisively with the Donatist issue in North Africa. Under Diocletian persecution (which Constantine officially ended), many Christians had succumbed to fear and handed over copies of the scriptures to the authorities. They were considered traditores, from which we get the word traitor. As far as the Donatists were concerned, the traditores did not belong in the church. If you had been baptized by a traditore, they insisted, your baptism was invalid—which led some to be rebaptized.

After Constantine Christianized the empire early in the fourth century, he dealt decisively with the Donatist issue in North Africa. Under Diocletian persecution (which Constantine officially ended), many Christians had succumbed to fear and handed over copies of the scriptures to the authorities. They were considered traditores, from which we get the word traitor. As far as the Donatists were concerned, the traditores did not belong in the church. If you had been baptized by a traditore, they insisted, your baptism was invalid—which led some to be rebaptized.

The newly Christianized Rome ruled against the Donatists and ultimately punished rebaptisms with the death penalty. Taking his cue from Constantine's Rome, Zwingli had the Anabaptists drowned in a cruel mockery of their belief.

The act horrified Luther, who wrote:

"It is not right, and I am deeply troubled that these poor people have been put to death so cruelly. Let everyone believe what he will. If he is wrong, he will have punishment enough in the fires of hell. Unless they are seditious, one should contest such people with God's Word and the scriptures. You will accomplish nothing by executions."

After the horrific excesses of the Inquisition, Luther's thinking was a breath of fresh air. Not to suggest that the Anabaptists were actually heretics—or “tares”—but Luther's approach was a return to the advice given by Jesus Himself in the parable of the wheat and the tares:

"The servants said to him, 'Do you want us then to go and gather them up?' But he said, 'No, lest while you gather up the tares you also uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest, and at the time of harvest I will say to the reapers, "First gather together the tares and bind them in bundles to burn them, but gather the wheat into my barn."'" (Matthew 13:28-30)

Luther believed that if the Anabaptists were wrong, it was best left to God to sort the matter out.

The religious liberty we take for granted was hard won, and slow to develop. Of all people, Christians should be among the most vigilant to be sure that it is not lost—for anybody.